The Assimilation policies in Australia began in the Forties and the period ran till 1965. This was a policy that determined how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should have the same rights and privileges and responsibilities as other non-Indigenous Australians, and be made essentially indistinguishable from non-Aboriginal Australians.

These policies, however, had a very western lens. Government ‘training programs’ were offered that focussed on agricultural or pastoral skills for men, and domestic or service skills for women. For those that stepped out of this model and sought semi-professional or professional roles such as nursing, systemic racism was faced daily. Segregation was still common. Indigenous people could still be made ‘wards of the government’ if they were thought to be living in a non-similar manner to non-Indigenous people, were perceived to not manage their own affairs, have different social habits and behaviours, and personal associations. Basically they had to be ‘just like white Australians’ and if they were not, the government could step in.

My grandfather, who served to fight wars for this country when he was not yet a citizen and came back to a segregated land where he couldn’t even share a drink with his digger mates in the pub because he was black.

My great grandfather who was jailed for speaking his language to his grandson – my father – jailed for it!

My grandfather on my mother’s side who married a white woman who reached out to Australia, lived on the fringes of town, until the police came, put a gun to his head, bulldozed his tin humpy, and ran over over the graves of the three children he’d buried there…

You might hear tonight, ‘but you have white blood in you.’ And if the white blood in me was here tonight, my grandmother, she would tell you of how she was turned away from a hospital giving birth to her first child because she was giving birth to the child of a black person.

Stan Grant (2015)

‘But every time we are lured into the light, we are mugged by the darkness of this country’s history’, Ethics Centre IQ2 debate

In relation to women and families, a 1965 amendment to the policy of Assimilation meant that the authorities could forcibly remove children from their families on very flimsy grounds, leading to the ‘Stolen Generation’ and untold trauma. The devastation these policies caused, together with the segregation/protection policies before, were well documented in the ‘National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, 1997, Bringing Them Home (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Sydney)’. Violence and neglect was rife in the children’s homes that some children were sent to.

The health of Indigenous people continued to suffer under this policy, as cultural and social welfare continued to be neglected. Toward the end of this period, however, there was more information about the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people, and some recognition of the terrible state of health. Today, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people still have the memories of their relatives being removed from their families, and indeed, many people alive today are those very victims. These memories are often not too far away from Indigenous women giving birth in our hospitals and birth centres today, often unable to access birth care in their own community.

Profiles

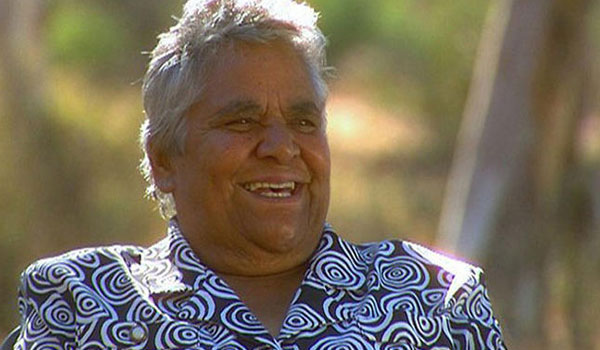

Voices from the Armchair: Aunty Pamela Mam

Deadly Choices honour the life of Institute of Urban Indigenous Health patron Aunty Pam Mam

Pamela Mam {Qld, 1938 – 2020}

Resources

Birthing Business in the bush

Timeline of Trauma and Healing in Australia

The Healing Portal

Florence Onus. Telling Our Stories – Our Stolen Generations

Florence Onus shares her story of being the fourth generation of her family institutionalised and forcibly removed, and her healing journey © The Healing Foundation

Faye Clayton. Telling Our Stories – Our Stolen Generations

Faye Clayton shares her story of being one of six children forcibly removed from her family of nine, and why donating blood is an important symbol for her. © The Healing Foundation

What can you tell us about the Assimilation and breeding out programs?

Colin Jones, lecturer in Aboriginal History, talks about his culture and history, and the underlying philosophy of the assimilation policy. © Qld Rural Medical Education Ltd